4 Mass spec history

4.1 1890s-1920s: Early developments

4.1.1 Cathode ray tubes

In the 1890’s scientists worked to understand atomic structure. This exploration eventually lead to the discovery of cathode rays specifically to determine mass, which we now call electrons. In probing cathode rays he deflected them magnetically or electrically, and then compared the heat generated when they hit a thermal junction. The deflection allowed him to calculate mass and the heat generation allowed him to calculate energy. By discovering these subatomic electrically charged particles he won the nobel prize for this in 1906

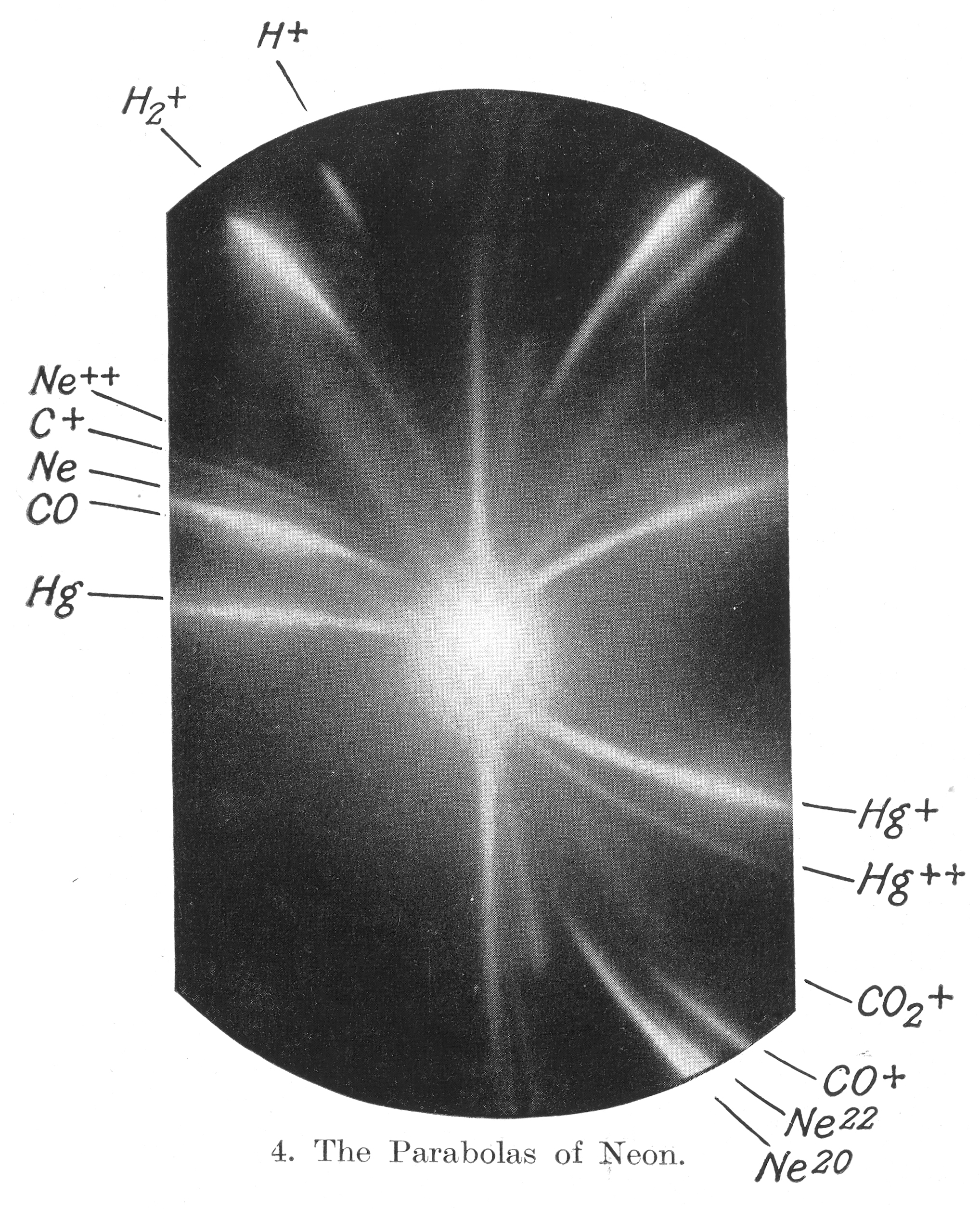

JJ Thomson continued this work with his research assistant FW Aston. They would deflect accelerated gases using a magnetic and electric field and measure that deflection using a photographic plate in the path of the ion beam (Figure 4.1). The physical dispersion was measured and due to the presence of two dispersion paths the two stable isotopes of neon were discovered in 1912, the first time stable isotopes were measured. The glass apparatus that the subatomic particles were accelerated through is a cathode ray tube, and is a predecessor to the modern day mass spectrometer. Aston continued the work combining magnetic and electronic separation increasing the mass resolving power of the instruments .

4.1.2 Electron impact sources

Alternatively, in 1917 AJ Dempster published a work on positive rays largely considered to be the first description of an electron ionization source (Dempster 1918). He directed a positively charged beam at a solid surface generating ions he could determine a mass to charge ratio. He continued this work and eventually determined the stable isotopes of lithium and magnesium using this technique. Furthering the techniques developed by Dempster, W Bleakly was able to generate a monoenergetic beam of electrons to ionize gases in 1929 (Bleakney 1929). The beam in this type of instrument traversed a 180 \(^\circ\) magnetic field and was deflected in a circle to the detector.

4.2 1930s: The first mass spectrometers

Due to the size and complexity of the 180 \(^\circ\) magnetic field early spectrometers, they were difficult to build and maintain making them a relatively rare tool. In 1940 A Nier developed a mass spectrometer in which the ion source and the detectors were removed from the influence of the 60 \(^\circ\) magnet. These sector field mass spectrometers greatly reduced the power consumption of the instruments, decreased complexity, and did not decrease the mass resolving power. With the knowledge that was gained during the war expansion, he published his seminal paper in 1947, describing the basis of most mass spectrometers that are still used today (Nier 1947). The Nier-Johnson or double focusing mass spectrometer combined the sector magnet with an energy filter allowing for pure separation by mass, a design that is still the norm for high mass resolution instruments.

4.3 1940s-1950s: The Manhattan Project and World War II

World War II greatly accelerated the pace of scientific development in physics and chemistry as world powers competed to develop new weapons, production techniques, and energy sources. While international collaboration and public dissemination of research ground to a halt during the war years, scientists continued working in secret on much of the same basic research—alongside a focus on applications to wartime policy goals, particularly nuclear weapons development. During the war, massive industrial operations like the Manhattan Project focused on isotope separation technology and the physics of nuclear decay and chain reactions. After the war, many of the scientists who worked on these projects returned to basic research, publishing a wave of new publications based on previously secret wartime research. These developments in the late 1940s and 1950s laid the groundwork for the modern field of isotope geochemistry by bringing the tools of nuclear war to bear on chronology and chemical processes in the geosciences.

4.3.1 The Manhattan Project

Nuclear weapons require a sufficient mass of concentrated fissile material (known as a critical mass) to maintain a nuclear chain reaction. Obtaining a critical mass involves mining and chemical separation of uranium and subsequent isotope enrichment to obtain an enrichment of at least 5.4% uranium-235ref (usually much higher), which is the level required to sustain a chain reaction. The critical mass depends on the activity of the fissile species and its concentration or grade. For example, the critical mass of a sphere of metallic uranium-235 is around 50 kg, whereas for plutonium-239 it is only around 10kg ref. At 20% enrichment of uranium-235, the critical mass is well over 500 kg ref.

In addition to understanding the parameters of criticality and sourcing raw materials, the success of the Manhattan Project depended on achieving sufficient enrichment of fissile species. Natural uranium is about 0.7% uranium-235, and while enriching it to just over 5% provides the theoretical possibility of criticality, weapons charges with masses in excess of a ton are impractical. A standard definition of “highly-enriched uranium” is over 20% uranium-235 ref, but in practice weapons-grade uranium is usually over 90% uranium-235.

Uranium isotope enrichment can be performed in multiple ways, and most modern enrichment facilities use gaseous diffusion of UF\(_6\) in a chain of gas centrifuges to gradually separate the heavier and lighter natural isotopes of uranium ref. However, the first uranium bomb produced during the Manhattan Project (the “Little Boy” gun bomb) used uranium produced by the Calutrons in the Y-12 enrichment facility at Oak Ridge ref. The Calutrons, so named because they were developed by Ernest Lawrence at The University of California and used large magnets originally built for cyclotrons, were essentially enormous mass spectrometers in which UCl\(_4\) was ionized by hot filaments and then separated by travel through a magnetic field, the same way a mass spectrometer mass analyzer separates isotopes. However, rather than measuring nA and smaller ion beams using sensitive electronics, the Calutrons collected grams of enriched uranium from ion beams in the tens of mA in graphite collector cups that were later burned to allow recovery of the uranium metal ref.

4.3.2 Postwar science

After the conclusion of the war, the physicists and chemists who had worked on the chemistry of isotope enrichment and the physics of nuclear weapons returned to other realms of basic and applied science. The same physics understanding that allowed scientists and engineers to construct nuclear weapons contributed to an understanding of the decay of radioactive nuclides to produce enrichments in radiogenic daughter products in natural materials, which is the basis for radiogenic isotope geochemistry. The principles underlying the chemical separation of isotopes, whether through electromagnetic separation or gaseous diffusion, applied as well to the separation of isotopes through natural geochemical processes, which is the basis for stable isotope geochemistry.

Technological developments

In addition to the boosts that the underlying science of geochemistry received from the Manhattan Project, the early mass spectrometers pioneered by AO Nier and others benefited directly from the work on Calutrons and other scientific and industrial instruments during the war years. Rapid advances in vacuum systems and instrument design occured in this era. John Reynolds introduced the static vacuum noble gas mass spectrometer in 1956, dramatically improving the sensitivity of these instruments and paving the way for realistic measurement of noble gas samples from rocks and minerals ref. This in turn enabled the rapid growth of the K/Ar dating technique, which allowed geochemists to produce a quantitative Geologic Time Scale and which dominated the next several decades of geochronology before being largely displaced by the related \(^{40}\)Ar/\(^{39}\)Ar technique and U/Pb geochronology.

4.4 1960s-1970s: Diversification of techniques

4.5 1980s-1990s: Commercializaiton and plasma sources

Houk et al. (1980) and Date and Gray (1981) developed inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Gray (1985) coupled ICP-MS with laser ablation (LA) systems (as a sample introduction). Soon after their development ICP-MS (in 1983) and ICP-MS coupled with LA (1990) became comercially avaialble and experienced great improvements, which made them one of the most dominant techniques for trace, ultratrace and isotope analysis.

The development of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS) and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) Tanaka et al. (1988) enabled soft ionization large biomolecules. Earliest succesful analyzes on biomolecular on macromolecules using soft ionization published in late 1980’s (Fenn et al. 1989, 1990). Fenn and Tanaka (together with Wüthrich) received the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 2002 ((https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2002/popular-information?)/.). Nowadays, MALDI and ESI are soft ionization techniques that are combined with various mass analyzers to analyze proteins, peptides, syntheic polymers, small oligonucleotides, carbohydrates andlipids

THe rapid improvements and development were triggered by extensive application fields, which included investigation of the hazardeous waste disposal (approved by US Enviremental Protection Agency), space explorations ((https://science.nasa.gov/mission/galileo-jupiter-atmospheric-probe?)/)

: